There’s no better way to start this new content series than by discussing movies many people find dull and unstimulating — movies portraying everyday life. In this (sub)genre, the audience is presented with patient slice-of-life pictures, provocative conversations, or simply observations of human relationships. To me, these films have their beauty that’s solely theirs. Beauty in emotional catharsis, life’s Sisyphus tendencies, or the inherent pleasures of life itself. When given an honest chance, these lyrical dramas are hauntingly evocative.

To preface the rest of this essay, I want to point out that I’m unsure of what I’m trying to accomplish with this piece. It could turn out to be a comparison of similar cinematic styles throughout the last century. Or how directors of different eras used cinema to mirror reality. Who knows. I’m a huge fan of all the directors noted below, and the one thing that ties them together is their appreciation of telling the ordinary story in their own exquisite way.

Past

Let’s start by going back over half a century. Back to the post WW2 era but more specifically to 1940’s Japanese cinema. Comparatively, other nation’s were experiencing their own cinematic movements — neorealism in Europe (rightfully influenced by Japanese neorealism), the rise of noirs and Orson Welles in the States — yet one can argue that during this decade around wartime, Japan produced some of film’s most influential pictures. The cinema of Postwar Japan has one helluva personality. The nation was rebuilding itself economically and culturally, introducing urban centers and a middle class echelon as well as an appetite for Western, French, English, and even German pop culture. This sudden transition in society came with its own battles. How does Japan balance Westernization with its beloved traditionalism? What are people’s roles in this new environment?

In all of cinema, no one has been quite as influential as one of the original masters of realism: Yasujiro Ozu. There is no shortage of literature about this pedagogue of timelessness; so much literature that I can write another essay about some of my favorite films of his and his unique cinematic style. But for this essay, we’re going to sample his oeuvre for the resounding themes of daily life. His work spanned all the way from prewar to interwar and ended with postwar undertones, from which two theses stood out — one regarding the fraught, complex, cross-generational relationships and the other of the role of traditions, specifically marriage, in society.

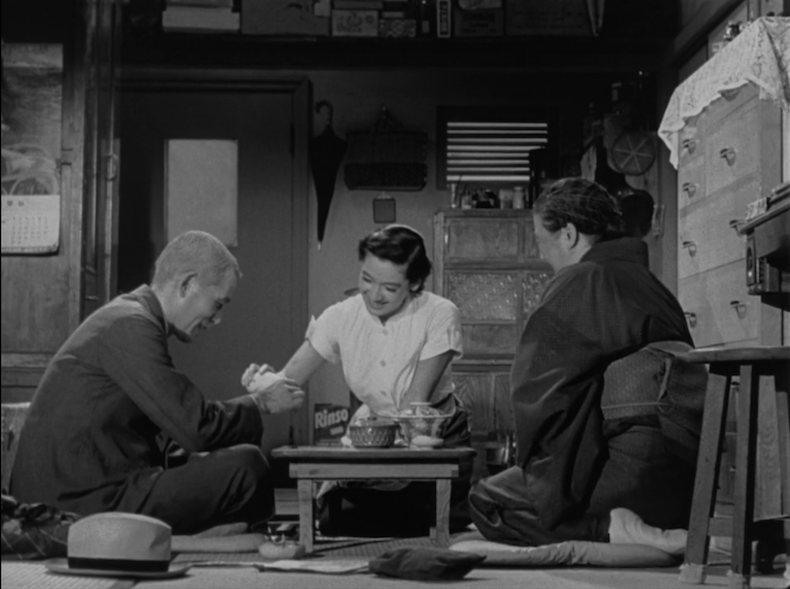

Screenshot taken from Tokyo Story (1953)

Screenshot taken from Tokyo Story (1953)

A fitting place to start is with what many consider his magnum opus, Tokyo Story (1953). Parents from the countryside make a trip out to Tokyo to visit their children. What they don’t realize and what the film scrutinizes is how a modern adult life can strain familial relationships, bonds fray by what can be interpreted as selfishness, obligation, or independence. Ozu obesses over the family dynamics – parents making enormous sacrifices, children being children, and how the relationship between the two changes over time. In The Only Son (1936), we see the morbid repercussions of war, poverty, factory jobs, etc., but we also see how these place strain a family, forcing parents to make extremely difficult choices for the sake of their children’s futures.

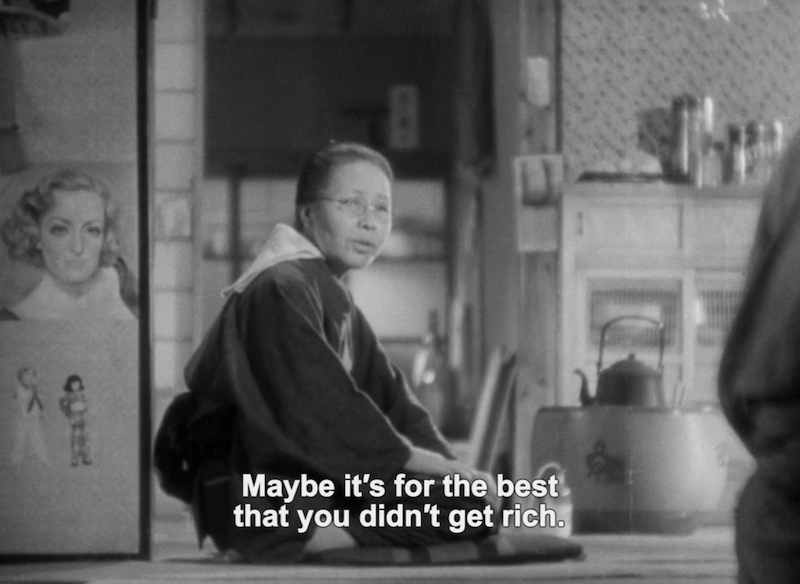

Screenshot taken from The Only Son (1936)

Screenshot taken from The Only Son (1936)

A mother pushes herself to ensure her son receives an education in Tokyo, but he struggles to provide even meager hospitality despite his degree. In Tokyo Story, a film made nearly two decades later, we note a similar observation of family relationships. The parents who are in town can only spend brief moments with their children, even after their laborious trek into the city. Their biological children, an overworked doctor and a hairdresser, jobs fitting for the time, barely spend any time with their parents to the point where the responsibility falls on Noriko (played by the adored Setsuko Hara), a widow of the youngest son who died in the war. Noriko serves as a prism for Ozu’s contemplations about parenthood and the difficulties of nuturing a family. The parents empathize with Noriko, and it is through her that we understand family obligation, elderly loneliness, and a search for contentment with life. Ozu’s cinematography reflects these internal examinations, choosing seemingly repetitive frames, interiors, and cuts while emphasizing how dailyness, its delight and sorrows, powers existence.

I also want to quickly cover another of Ozu’s themes: deciding if and when traditionalism matters. Nearly all of his movies were imbued with Japanese tradition and culture; many discussing the nation’s perspective of marriage, especially in regards to the woman’s toils. Films such as Late Spring (1949), The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952) (somehow my first Ozu), and Autumn Afternoon (1962) demonstrate how at the time, and honestly still today, the Japanese people held a strong opinion that unmarried women should always actively seek to become married and that their happiness is at stake if they choose solitude (independence). This is a concept I want to further explore, but let’s leave it for another essay.

Another director from this era worth highlighting is Mikio Naruse. His films are every bit as sentimental as his peers and deserve more recognition in the West. I have yet to thoroughly examine his immense body of work (90 films in under four decades), but from the two I’ve watched, I can say he too deeply understands the complex nuances of life. He is often compared to Ozu for being another director of shomingeki (dramas of commonwealth), though his style and choice of stories told are as different as the sun and the moon. Naruse is regarded as a director with especially deep compassion for women. While Ozu made some movies showcasing the struggles of women enduring the rigid Japanese traditionalism, Naruse had headstrong heroines drive his narratives.

Screenshot taken from Yearning (1964)

Screenshot taken from Yearning (1964)

Time and time again, we see them struggle and wrestle in place, “yearning” for independence but through a comparatively modern lens. Women in his movies aren’t bound by the obligation of marriage as they are in Ozu’s, but are bound by the maladies of society, common and unfortunate acceptances of life back then. Even in the modern day, almost a century later, women can feel stifled in many, seemingly ordinary interactions. It’s as if the traditions and social norms have changed, yet societal pressures and their consequences have remained.

Present

The world has experienced astronomical growth and development in the past few decades. Grateful for technology, we, as a society, have become empowered like never before. Communication and opportunity are the most open and accessible they have ever been. As a society becomes ever-increasingly complex, it’s important to consider how our relationships with ourselves and others can complicate in turn. Alongside that examination is one more fatalistic. When reflecting on the past, how can we know if we’ve lived an unregrettable life?

No one has better answered these questions than Taiwanese New Wave icon, Edward Yang. His final film, Yi Yi (2000), set in a rapidly Westernizing Taiwan, focuses on a four person family. More accurately, it delves into the four distinct stages of life that the characters experience.

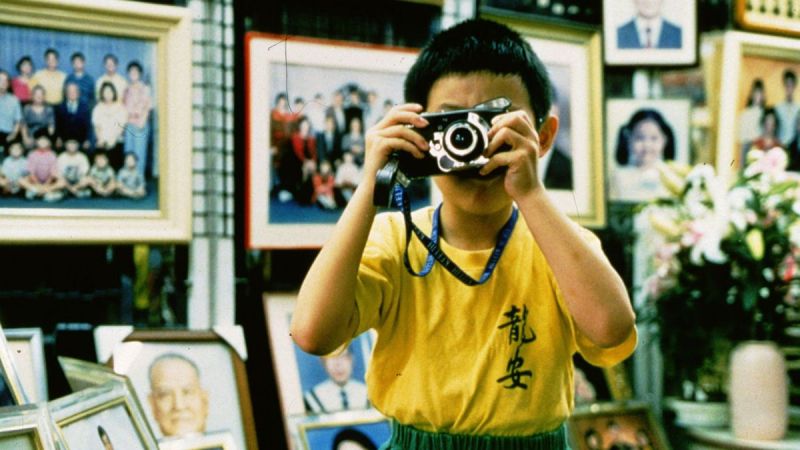

Screenshot taken from Yi Yi (2000)

Screenshot taken from Yi Yi (2000)

In three, compact hours, we experience youth, adolescence, middle age, and death. Yi Yi presents the understated pensiveness and melancholy rooted in the core of our lives. How regrets lingers. How we can never look back not because we shouldn’t but because we cannot forget our past. Many adults are afraid of living an unfulfilling life. NJ is dissatisfied with his job and reconnects with an old flame to try to make sense of his unresolved past. His wife, Min-Min, wants to understand the meaning behind her mother’s death. All the while, children are busy discovering the beauties and dangers of the world. Ting-Ting is bit by the snake of young love; Yang-yang (my favorite character and likely the voice from Yang’s youth) is left to his own devices, soaking up his surroundings. I could talk about this movie for hours on end, so let’s wrap it up here. Yang is one of the best; his films are somberly composed. What we see is merely daily life. What we feel from it is so much more.

Now, back to the Japanese flavors. Whenever Ozu is discussed, people tend to compare him to one of Japan’s living, actively working legends, Hirokazu Kore-eda. I think to call Kore-eda the next Ozu is a farfetched claim. Their stories are completely different. Ozu focused on the intricacies of the postwar Japanese zeitgeist while Kore-eda seeks to understand the connections between people, their experiences and grave emotions, in a modern, honest way. Ozu employs his unique camera work to capture a feeling of timelessness and transcendence while Kore-eda’s cinematography is dynamic to underline imperfect, interpersonal connections. Kore-eda is a Japanese director (I almost said auteur, but he hates that term) who embodies the current, 21st century metaphysics of life in today’s social struggles, friendships, and family life.

Kore-eda says himself that “he enjoys being an observer, and his films are what he sees.” He debuted in the mid 90’s and has been presenting audiences his observations of the modern day. In what is considered his most expressive work, Still Walking (2008) revolves around Ryota, the younger son, visiting home to honor the anniversary of the oldest son’s death (Kore-eda enjoys using death as a motivator, in both plot and character). However, he returns home only to quarrel with his father, who feels disappointed by Ryota. The movie’s central conflict lies in the father’s and son’s inability to reconcile their differences. Like father, like son I guess.

Screenshot taken from Still Walking (2008)

Screenshot taken from Still Walking (2008)

Kore-eda uses natural elements to convey these human ideas. An ocean, grid-like streets, cooking generational recipes. These and more showcase the frustration, regret, and pride of our average family. He has also covered other aspects of family life. In After the Storm (2016), he investigates the emotional and psychological struggles of a divorced father (also named Ryota and also played by Hiroshi Abe). He finds himself in a rare circumstance. Confined to a single apartment with his ex-wife and son, waiting for a typhoon pass. He stubbornly uses this time to attempt to rekindle a flame with his ex-wife, promising to be a person he knows he can never be for her. Ryota, like many men today, is headstrong, chasing after something already beyond his reach, only to never find it or any semblance of redemption. Portrayed tenderly and honestly, he, and the rest of the family, feel like people who anyone can meet on the street. Maybe I’ll have a chance someday. To Kore-eda, a tender humanist, to portray the present is to portray interactions between those close to you, no matter how exasperating they may be.

There are too many directors who make movies that faithfully render the present, but if I take the time to discuss even one more, the essay will be far too long. So for now, let’s turn our attention to the future!

Future

When imaging the future, people often overestimate the grandeur of their later years, the growth of technology and their internal satisfaction. Nothing against being optimistic, for I, too, like to dream big. But, when we relate this mindset to the world of film, we can see that there has been an explosion of sci-fi, CGI employed, animated, and other more magical forms of film, seeing how we have modern tools to do so. In my opinion, these movies serve as a form of escapism, visual candy for the eyes and ears, but when the world has too much of this kind of content, it starts to forget one of the film’s original purposes — to tell a story. The world as we see it is full of compelling stories. We just have to stop and smell the grass for a second.

Today, slower paced movies mired by quotidian moments are hard to come by. The style has been close to entirely replaced by a dynamic counterpart, but luckily, a few quiet heroes remain.

Screenshot taken from Columbus (2017)

Screenshot taken from Columbus (2017)

After discussing directors of the likes of Ozu and Koreeda, I would be remiss if I were to forget this man. A lauded video essayist with a moniker inspired by Ozu’s very own screenwriter, Kogonada has recently burst into the directorial scene. His visually stunning feature debut, Columbus (2017), gives me hope for this lullaby of a movie genre. On the surface, this film is another romantic drama. A middle class family in the midwest and an absentminded visitor. But as layers of conversation peel back, the film transforms into a pithy investigation of uncertainty and strife. Kogonada is reminiscent of his inspirations as evinced by his meticulous shot selections, choice of camera movement, and portrayal of the mundane. Though his story isn’t the most unique, his depiction of an average family gives me hope that champions of this style of cinema still remain. An homage to the static shot loving, conversation centric forefathers and a reminder that patience is a virtue. I can’t wait for After Yang.

One other (wildly underseen in my opinion) director to highlight is the quirky, elusive man, Jim Jarmusch. A primary force in Western Independent cinema, Jarmusch’s films seek to understand the cause and effect of seemingly simple behaviors and interactions. Admittedly, most of his films (Dead Man (1995), Only Lovers Left Alive (2013)) fail to discuss the aforementioned subject in similar cinematographic style, but there are a couple that do, and do rather elegantly (Mystery Train (1989), Stranger Than Paradise (1984), and Paterson (2016)).

How about we take a look at Paterson, the movie and the sleepy New Jersey city. On the surface, the story is as ordinary as they come. A bus driver wakes up every morning. Goes to work. Walks his dog to the local bar. Spends his spare time writing free verse poetry. However, as the movie progresses, the audience begins to realize, through subtle feeling alone, that this week is different. It’s days, when linked together, become far greater than what we had initially thought. The moments, not some rollercoaster plot, dictate the narrative, allowing us to focus on the poetic beauty and virtue of everyday life.

Screenshot taken from Paterson (2016)

Screenshot taken from Paterson (2016)

Jarmusch takes his time to let us notice what Paterson notices and sit with the reticent poet in his thoughts. The couples of images and bodies that pass him. A man attempting to win back his girlfriend. The height of the action comes when his bus breaks down, and as an audience, we find ourselves increasingly invested in him. The average landscape of a small Jersey town is no backdrop for the typical Hollywood hero’s journey but one for coloring the humdrum of life. Repetitiveness doesn’t always lead to sorrow, but instead, leads to recognition and thus appreciation for what you have and who you are.

So what makes Paterson such an immersive watch? I would say that it’s one part relatability, one part the familiarity of routine, and possibly one part learning to understand his stoicism towards his surroundings, finding solace in how his life dictates his craft. Jarmusch also find moments to criticize (speaking mainly through Paterson’s wife) how superficial and contrived creating content today has become. This film is a testament to how creating art should return to its innate form of self-expression, something I hope directors in the future never forget.

These two directors represent the future in contrasting ways. Kogonada’s career has yet to be realized. He has an entire canvas of life ahead. Jarmusch, an established director, continues to experiment and tell the stories that he wants to tell. Both of them, however, try to answer a few questions I find myself asking about films in the future. How do we continue to capture beauty in the ordinary? Do we seek it in the portrayal of normalcy? Or has it and always will be right in front of us, waiting patiently for our attention? There’s nothing more we can do than to appreciate what surrounds us with a settled heart and earnest eyes.

“I’m trying to find a Zen way where you are just there each moment and you’re not thinking too much about what’s going to happen next” - Jim Jarmusch

Honorable Mentions

There are many more directors who I considered when writing this essay. Some produce film with similar distinct qualities, primarily a shared naturalistic style, to the few mentioned here but construct their narrative more so around character conflict than around internal strife or the unavoidable burden of life. I could honestly put so many more directors on the list below and say so much more about the directors above that I’ll probably end up writing another essay about realist films.

- Hiroshi Shimizu

- Shohei Imamura

- Akira Kurosawa

- Dardenne Brothers

- Ken Loach

- Mike Leigh

- Hou Hsiao Hsien

- Robert Bresson

If there’s anyone you recommend I watch or anything you’d like to discuss in more depth, feel free to reach out to me on twitter. I’d love to chat!

Cover Photo: Cute lil Yang-yang from Yiyi.